Gardens resonate as a world archetype of goodness. Many societies depict paradise as a garden, sweetened by the sound of a fountain’s water splashing on blue tiles, immortalized in the floral enclosures of lush Persian prayer rugs.

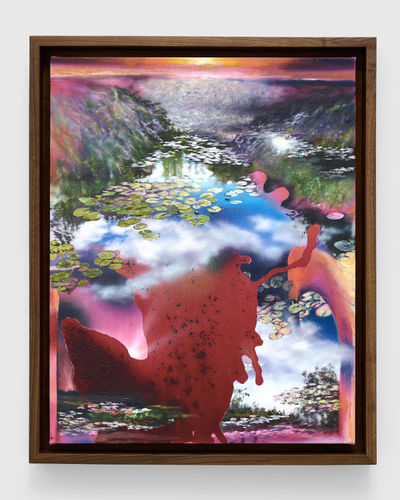

And gardens, disrupted and deconstructed, perhaps carrying an element of the fountain’s droplets, inspired “Unwilded,” a new series of eight intimately scaled paintings by Annie Lapin, now on view at the Nazarian/Curcio gallery through November 2nd.

Last week we visited Lapin in her light-drenched Eagle Rock studio where she’s at work on further explorations of the conversation between nature, human nature, technology, and paint.

“I start with the pour,” she says. Lapin mixes acrylic paints and liquid graphite into a small container, perhaps a recycled plastic cup, and then lets gravity and physics do the rest by emptying the cup onto a pristine canvas, splattering and spattering, spilling and dripping.

“It’s like a Rorschach test,” she says. Like seeing the face of The Blessed Virgin Mother in a burned tortilla, or ships and unicorns in the clouds, Lapin says “Different people see different things in the pour.”

“From there,” she says, “I research online, photographs and iconic works of art. I sometimes do an initial composition on the computer, using Photoshop and my own memory. I paint around the pour in an intuitive way, referencing classical landscapes but shifting the visual perspective.”

Lapin earned her BA at Yale, her Post-Graduate Certificate from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and her MFA from UCLA.

Lapin is the recipient of the Falk Visiting Artist Award at the Weatherspoon Art Museum in Greensboro, NC and she has been awarded residencies at Anderson Ranch Art Center, Snowmass Village, CO; Grand Arts, Kansas, MO; Burren College of Art, Ballyvaughan, Ireland; and Chautauqua Institute, New York, NY. Her work has been featured in Art in America, Modern Painters, Los Angeles Times, Harper’s Magazine, Art and Antiquities, Artnews, Hyperallergic, Artsy, and New American Paintings.

Lapin’s work is included in the permanent collections of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; The Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum at California State University, Long Beach, CA; Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, KS; Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA; Rubell Family Collection, Miami, FL; Santa Barbara Museum, Santa Barbara, CA; Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC; and Zabludowicz Collection, London, England.

Artist Annie Lapin in her Eagle Rock studio. Photo: V. Thomas

Artist Annie Lapin in her Eagle Rock studio. Photo: V. ThomasAs urbanites, many of us yearn for a forgotten or simply imagined time when the world was wild. The notion is often expressed that our ancestors took delight in the unspoiled earth.

But let’s not kid ourselves: floods, fires, famine, fevers, fears, and fleas defined human life at the mercy of the elements, or the gods.

Sure, our forebears were no doubt grateful for rain falling soft upon their fields, good harvests, salmon in the river, and another generation of spring lambs. But the first Europeans who arrived in North America viewed the land itself as far from paradise.

In the Torah, which perhaps ironically informed the religious life of the newly arriving Puritans, wilderness (as in desert) is depicted as a place of separation, exile, testing and judgment. The naked-and-afraid motif is carried forward into the New Testament as well. Moses wandered for 40 years, while Jesus fasted in the desert for 40 days and was unsuccessfully tempted by Satan.

The first white settlers viewed the untouched canopy of sassafras, beech and maple of the American Northeast as perilous chaos, wild and unruly, as The Chicks sing. Heeding the word of Genesis 1:28, admonishing us to take dominion over the earth and subdue it, Puritans viewed the forest as a manifestation of lawlessness that easily invites the fleur du mal to flourish.

This fear of the wild is present in Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter” and Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible,” resonating with older stories of children being abandoned in the Schwarzwald to encounter a candy-proffering witch, of St. Olaf turning pagan priestesses into trees, and other long traditions of equating wildness with the demonic.

Unwilding the land, first for crops and grazing, then for trim, prim rose-courts and dainty beds of violets, topped the Puritan agenda as a crucial step in bringing order to the savage new place. Forcing the indigenous human beings already on the land to conform to European standards was also part of the program. Dreamy pastoralism would, of course, follow with Thoreau and Muir.

“Knowledge of what happens when land becomes property,” says Lapin, “is unstated but present in my work. Beautiful ideas, including ideas about order and civilization, fall apart when historical icons are stripped of their symbolism.”

These paintings reference famous gardens, including Monet’s at Giverny, where the artist diverted the River Epte, then planted wisteria, bamboo and of course the famous water-lilies just outside his back door.

“I began this pouring series in 2014 or 2015, when I was feeling a lot of climate anxiety, and also a lot more rage,” she says. “I wanted to introduce something spontaneous. I don’t describe my work as on-the-nose political, but each of these has its own spatial logic and tells its own story and re-contextualizes images which may be familiar to some.”

We risked offending the artist by mentioning that the random splash of paint which forms the basis of each work, juxtaposed against her precise, sometimes hyper-realistic renderings of famous gardens—she masks off the pour with brown paper and tape, then uses airbrush in other areas— may suggest art-vandalism, perhaps as an act of protest against fossil fuel, a redaction on court documents, or maybe an anarchistic Sharpie mustache scribbled on the Mona Lisa. Or it may even be a “Dexter”-ish forensic blood-spatter.

I personally had flashbacks of spilling a Diet Coke on a high-priced coffee-table book.

Not so much, according to the artist. “There are residues of memory, and distortions from the digital world, so multiple identities emerge.

These are visual koans,” she says.