Trenton Doyle Hancock's solo exhibition, “Good Grief, Bad Grief,” will be a reunion of sorts when it opens at Shulamit Nazarian gallery on Saturday — a recommingling of superheroes and villains who live somewhere between good and evil.

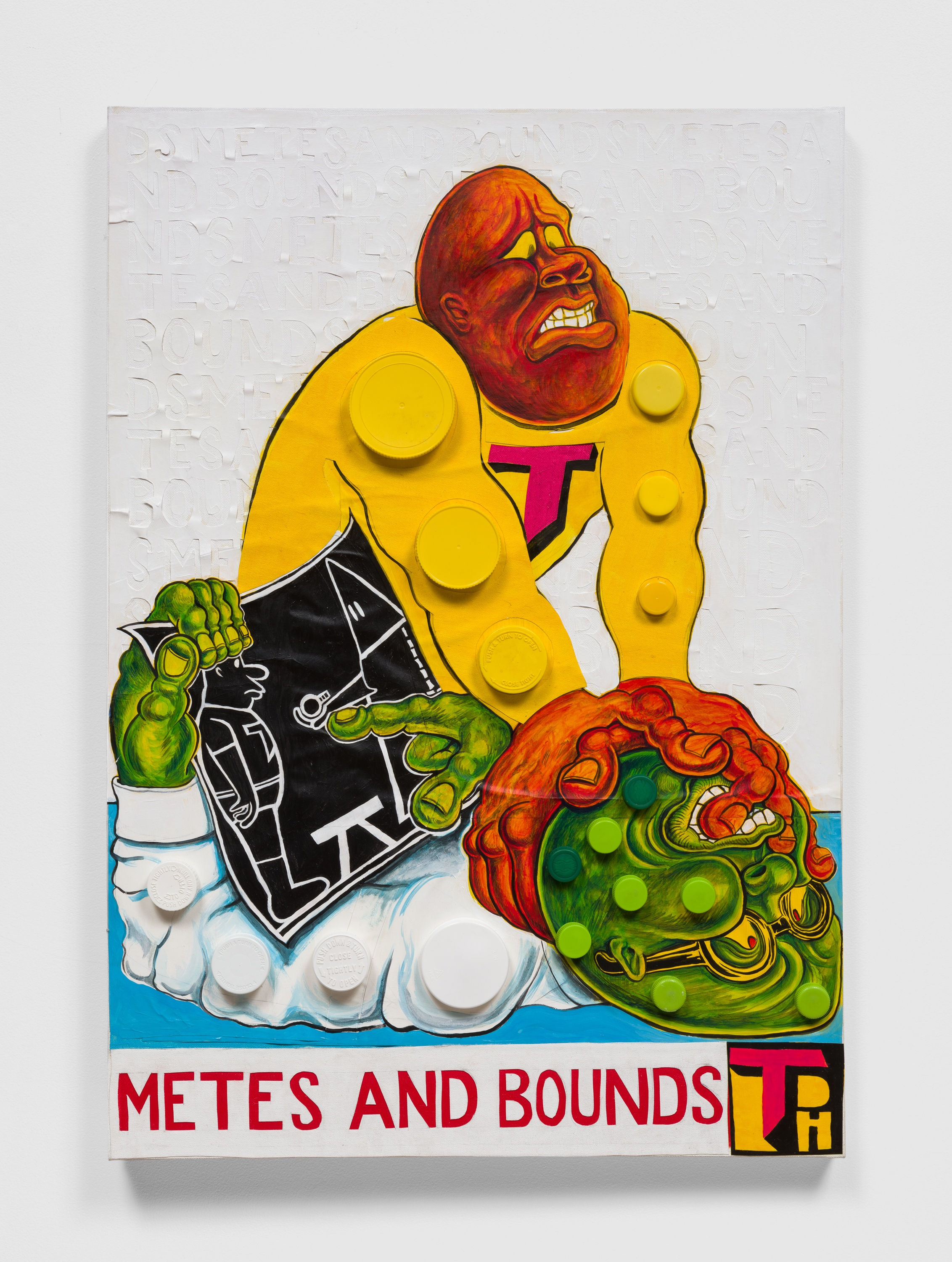

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s “Metes and Bounds” (2022). (Ed Mumford / Shulamit Nazarian)

The, Houston-Based Artist one of the youngest people ever to show at the Whitney Biennial at the time he participated in its 2000 and 2002 editions, works in painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking and performance — but more than anything, he is a universe builder. Over the last 25 years, he’s fleshed out a cast of comic-book-like characters that repeatedly appear in his artworks. Three of them come together in “Good Grief, Bad Grief,” the artist’s second solo exhibition at the gallery. The show both draws from and subverts traditional myth narratives while also exploring race, class, identity and power dynamics in America.

There’s Torpedo Boy, Hancock’s well-meaning but often wayward alter ego whom he invented in the fourth grade; there’s the bespectacled Hancock-the-artist, a more direct representation of Hancock; and there are the Vegans, a society of pale, emaciated-looking characters who work together toward the demise of the Mounds, a civilization of half-animal, half-plant characters that process negativity from the earth and emit color in its place.

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s “The Skint Alterpiece: Vegans Make Deposits at the Tofu Bank,” 2020. (Shulamit Nazarian)

“Step and Screw: Seven Foot Furry Face Off” depicts Hancock gripping a giant pencil and engaged in a face-off with Torpedo Boy. A klansman’s hood floats over a stool between them. The 7-foot-tall work, which is made from cut and collaged faux fur, is part of Hancock’s ongoing “Step and Screw” series, which speaks to power structures and white supremacy in America.

The exhibition also includes a chapter of Hancock’s in-progress graphic novel, which will be made up of about 1,000 pen-and-ink drawings over four volumes. The pages on view in the exhibition will be displayed on a giant grid with 19 drawings individually framed. The book project is Hancock’s attempt to give his unwieldy myth narrative — the Moundverse — a linear structure. In a way, it’s his attempt to make sense of his life’s work, he says in this edited conversation.

“Most of the book will be clearly grounded in fantasy involving monsters, mutants and super beings,” he says. “However, every third or fourth chapter will be based mostly in real-life situations that are embellishments on things that actually happened to me.”

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s “Step and Screw: Seven Foot Furry Face Off,” 2022. (Ed Mumford / Shulamit Nazarian)

What is happening between Hancock and Torpedo Boy in the painting “Step and Screw: Seven Foot Furry Face Off?”

The moment that you’re seeing in this piece was lifted straight out of my 2014 “Step and Screw” comic. In this comic, there’s a panel where my alter ego, Torpedo Boy, is facing off with one of Philip Guston’s Klan figures in a darkened room with a foot stool between them. The klansman is holding one of Guston’s iconic lightbulbs, and he’s handing it over to a visibly annoyed Torpedo Boy. I call this moment “The Exchange.” A few years ago, I began a series of expansions of the “Exchange” series by substituting one character in the place of another. With “Seven Foot Furry Face Off” I’ve replaced the klansman with myself, “the artist,” and instead of a lightbulb (symbol of ideas) he’s offering up the severed head of a klansman (or maybe it’s an empty hood?). There’s no clear idea of what happens next, and I prefer my pictures to end that way.

You grew up in a very religious household. To what extent has that informed your work?

I grew up in a fundamentalist Christian household with very strict rules that often clashed with my innate tastes. Even though I never fully believed in the truthfulness of the Christian mythos, its structure was nevertheless imprinted on me. Through my mother, stepfather and grandmother, and their rigor of ritual, I learned how to make speech, images and parables that feel succinct and important. I have hundreds of hours listening to songs and sermons to credit for that.

Even though I respected my family’s ways as clergy folk, I fought against issues of wholesomeness and purity in the only way I knew how, through drawing and painting. Even though I haven’t lived under my mother’s roof for 25 years, I feel as though I’m still rebelling against the Bible as I see it currently weaponized in state politics. In art school, I was required to study countless images of Jesus nailed to a cross, which were images I was already well acquainted with. This saturation in the motif prompted me to make my very own version of Jesus and the saints. I created the Mounds, Vegans, Torpedo Boy and the rest of my characters of consequence in response.

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s in-progress graphic novel, “Trenton Doyle Hancock Presents The Moundverse: Chapter 2 Veganism,” 2020. (Shulamit Nazarian)

Your graphic novel pages on view depict a clash between a society of Vegans, the police and several other of your characters. What is this a commentary on?

The Veganism chapter of my forthcoming graphic novel is a comical take on extreme behaviors whether it’s from a group of radical human vegans, an overzealous group of imaginary Vegans, a roided out [on steroids] superhero or a couple of magically corrupted police officers. This chapter also elaborates on how the power dynamics between two groups can change abruptly based on a variety of factors. While the Vegan chapter doesn’t fall easily into a specific political commentary, there is a statement about absolute power to be found (it corrupts absolutely, rinse and repeat).

Were you always a comic book fan growing up? What other pop cultural or art historical influences inform your work?

I was definitely a comic book fan growing up and I always aspired to make comics. However, at the collegiate level, I became interested in painting, animation and editorial cartooning. I often jump back and forth between these varied modes of making and I find that they inform one another.

How have your characters — and your myth narrative — evolved over time in response to your own life experiences?

I either paint from personal experience or I imagine circumstances that are possible or plausible based on a set of my own established rules. This allows for a broader writing/painting field than my own lived experiences. In many regards, I am the one who learns from my character’s experiences, not the other way around. I use my characters to gain a richer understanding of the world, and my narratives tend to prepare me for future life hurdles and inevitabilities.