A new generation of artists honors a photographer’s bold gestures—and envisions their own queer lineages.

Laura Aguilar, Plush Pony #15, 1992. Courtesy of the Aguilar Trust, Los Angeles.

Despite the nearby highway’s asphalt and concrete pillars, the overpasses and bridges, despite the litter and traffic noise, the Rio Hondo remembers, in the depths of night, to roll its fog into the San Gabriel Valley of Greater Los Angeles. Across the river, up its banks, the fog spills onto the 60 Freeway, carrying the water’s wet, green scent like a strange yet familiar song. The Rio Hondo carries still, in its damp breath, the ancient memories of its first Indigenous inhabitants, along with the Spanish missionaries it flooded and victoriously swept away. It remembers, as some people still do, the old barrios with families who bathed their babies and watered their horses at its rounded-rock beaches. Certainly, the river remembers the late Chicana photographer Laura Aguilar, who lived near its edge for much of her life and whose family had been rooted there five generations deep.

Aguilar grounded herself and her art in the natural landscapes she knew so intimately in order to express her difficult truths. As a lesbian who was fat bodied and struggling with a learning disability, she insisted on finding her way despite the sexism, homophobia, and racism that would otherwise erase her altogether. Aguilar endured personal hardships and the indifference of the art world toward her work for much of her life. Yet despite these obstacles, Aguilar’s vulnerability and persistent honesty allowed her to give view to her own life as well as the complex lives of queer people of color in LA’s Eastside and beyond.

WORDS

Aguilar pushed beyond the boundaries of her own comfort, driven by genuine curiosity and a spirit of inquiry.

In much of her work, Aguilar pushed beyond the boundaries of her own comfort, driven by genuine curiosity and a spirit of inquiry. As an artist, she sought to master the craft of photography and was known for her insistence on technical perfection while also using the medium to delve into complicated questions of identity and belonging. In the black-and-white series Latina Lesbians (1986-90) and How Mexican Is Mexican (1990), she photographed Chicano and Latino professional women in Los Angeles—experimenting with incorporating writing— to question how, and if, she fit into these communities. Aguilar also challenged herself to venture beyond her own circles of friends and acquaintances to photograph bar goers at an Eastside, working-class lesbian bar called the Plush Pony. Despite her own ambivalence as an outsider, she captured the venue and its patrons’ joyous yet guarded spirit. Here, as in most of her portraiture,

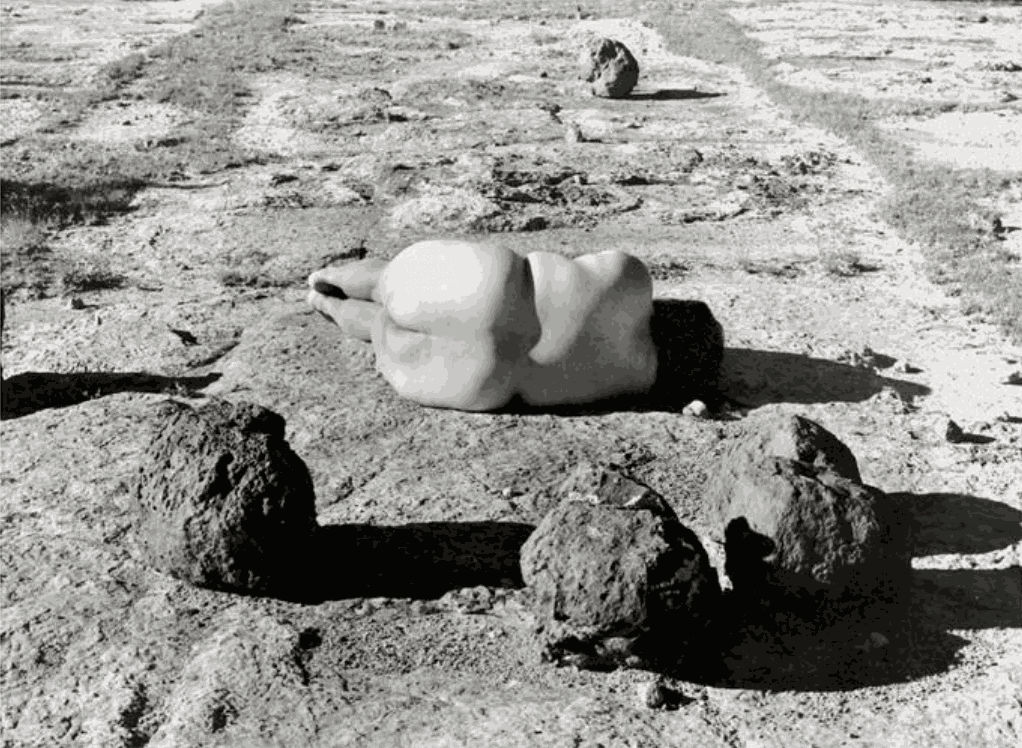

Aguilar tests herself against the safety of marginal spaces. By the mid-1990s, Aguilar’s nude self-portraits in nature give witness to her arrival at a way of being at home—with both her body and her historical lineage—through a strong connection to the land.

Laura Aguilar, Nature Self-Portrai #2, 1996. Courtesy of the Laura Aguilar Trust, Los Angeles.

Star Montana, Louisa, Cathy, and Little Star, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Though Aguilar remains intensely attentive to technical and compositional aspects in her Nature Self-Portraits (1996) and Stillness (1999) series, drawing influence from modernist traditions as well as direct inspiration from the work of contemporaries such as Judy Dater, she also finds a different way to be, positioning herself as an integral part of an ecosystem. Often posing by herself, or with other women, Aguilar reasserts her body, its shape and size, setting it in the context of the desert landscape as a way to belong to a natural and historical place. She affirms her personal and multigenerational relationship to California and collective narratives of the colonized West. Though Boyle Heights is often used as the poster child for gang life, this community has a long history of multiethnic activism and cultural richness despite poverty, discrimination, violence, and gentrification. In her 2019 series They Lost Us to Los Angeles, Montana’s images testify to the crucial bonds that are built through the gang lifestyle while also acknowledging its ruinous effects on young people and families. In one image, a young mother tags on a bathroom wall as she carries her baby; in another, a woman tattoos someone’s arm while her child observes intently.

Montana shows Aguilar’s first retrospective, in 2017, Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell at the Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM), housed at East Los Angeles College, was met with acclaim and enthusiasm, especially from the Latinx community. But this overdue homecoming at her alma mater was also received with some regret as the attention arrived when Aguilar’s health was deteriorating significantly. Aguilar died in 2018, shortly after the exhibition. Throughout her career, Aguilar had struggled with her learning disability, long bouts of depression, and worsening health complications due to diabetes. She found little support in the art institutions that largely ordain artists’ success, or lack thereof. In her 1993 series Will Work For, Aguilar condemned the exclusionary power of arts institutions that have historically ignored nonwhite and nonnormative artists like herself by standing in front of a gallery holding up a handwritten sign saying, “Artist Will Work For Axcess.”

However, following Aguilar’s VPAM retrospective, exposure to her art has awakened growing interest. Though Aguilar was known among her peers for decades, her influence has expanded as it continues to reach younger generations of Latinx artists as they uncover and rewrite their artistic lineages that are not centered on white or Eurocentric traditions. Instead of addressing monolithic identity issues, they delve into personal histories and place-specific ecosystems of their inherited and chosen communities.

Admirers of Aguilar’s work often note her perfectionism— people who knew Aguilar from her earliest days as a student photographer remember her unwavering commitment to mastering her craft. Mei Valenzuela, Aguilar’s teacher, mentor, and close friend at East Los Angeles College (ELAC), recalls imparting to her an important lesson. Having personally experienced the scrutiny of white male photographers and professors, Valenzuela advised, “You have to master your craft or they will tear you apart. You want technical quality so no one can put you down, and so they’ll have to deal with your subjects.”

Another Los Angeles-based photographer well served by Valenzuela’s mentorship is Star Montana. Also a former photography student at ELAC, Montana focuses on photographing residents of LA’s Eastside, capturing them in their daily lives. Montana, who grew up in the East LA neighborhood of Boyle Heights, invites friends and family to share scenes from their homes and neighborhoods.

With knowing intimacy, Montana uplifts stories of survival and resilience as she also grieves for the loss along the way that the body of the city is inscribed with the stories of its residents, as their bodies also carry stories grafted into their flesh. The artist communes with dirt, plants, and river water, for example, to reclaim some of the desert’s restorative qualities. He identifies ways to more fully embody his border queerness despite the pervasive violence experienced by queer men and boys, and undocumented immigrants, in this same environment.

Star Montana, Sunset (at the End of the Chihuahuan Desert), 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

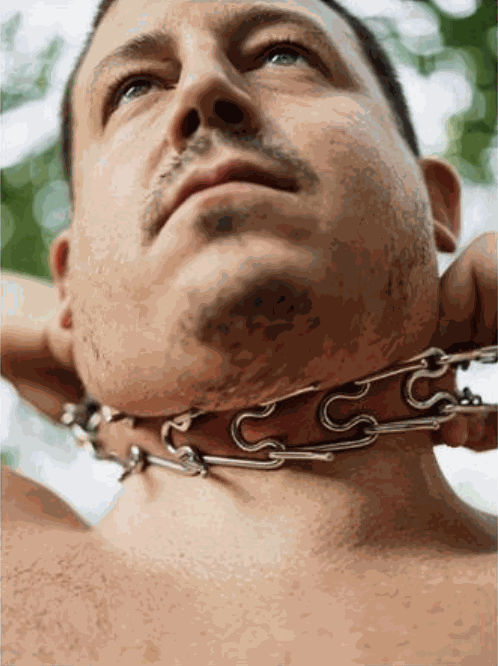

José Villalobos, Espuela Peligrosa (Dangerous spur), 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

In his ritual-like performance El Amor y su Entierro (Love and its burial, 2020), Villalobos kneels on dirt and runs the sharp spines of an aloe vera plant down the length of his tongue to signify both the silencing of queer voices and experiences and the act of healing that comes from telling one’s story.

Among her series of portraits, Montana features her own family’s experiences of loss and intergenerational trauma. Often using rescued family photographs, Montana diligently rebuilds an archive that also conserves its own destruction. Water damage gnaws on the edges of photographs and disfigures the images of her beloveds, along with those of a cast of strangers and lovers who vanished as quickly as they appeared in her life. “I wanted to keep the water damage. These are the ruins of diaspora,” she says.

Montana’s work sits patiently in the grief of displacement, measured in lost land or property, as well as the aching loss of connection to ancestral homeland and the unraveling fabric of family. The beauty of a sunset blazing at the edge of the Chihuahuan Desert can be read as a traditional landscape in which the viewers’ gaze is cast over seemingly yet-to-be-conquered territories. However, in Montana’s Sunset (at the End of the Chihuahuan Desert) (2018), the land bears a family’s story of displacement and trauma. Facing west, Montana presents a view toward Los Angeles, with awareness of the challenges her family would face there: “It’s aspirational but also terrifying, knowing the difficulty of this journey. I don’t romanticize.” She associates trauma with her family’s westward journey from El Paso, Texas, to Los Angeles following the death of one of her grandmothers. The loss was unbearable, and her family decided to uproot and start anew. However, the move was so disruptive and full of grief that Montana continues to mourn: “Our line was cut. It was the end of our connection to El Paso.”

In Aguilar’s life and art, Montana sees how she, too, can behold the pained individual and communal body. “I saw she was a depressed, poor, fat, queer woman. In photography, you can be one but not all of these,” says Montana, who considers Aguilar’s honesty her most important quality: “It’s not about ego or beauty. It’s about truth.” Montana finds resonances of Aguilar’s art in works by younger artists such as herself. On social media, she notes that people are actively practicing a diaristic approach to sharing their experiences as queer, poor, and brown youth, including their struggles with mental health and depression. “There are more platforms for us to see each other’s work, and it helps,” she says.

Aguilar’s nude self-portraits demonstrate that colonized bodies of color, like the land, can be sites of healing as well as sites of artistic regeneration. In Aguilar’s photographs, the performance and installation artist Jose Villalobos finds evidence of resistance and inspiration for his own work, which is centered on the queer male body. Raised along the El Paso-Juarez border, Villalobos often uses his body as a medium, alongside other natural elements from the landscape of the Chihuahuan Desert and the Rio Grande.

Villalobos pushes against heteronormative Mexican masculinities by reappropriating objects of norteno culture. Elaborately embroidered cowboy belts, boots, and buckles, along with equestrian paraphernalia, such as whips, chaps, and saddles, are deconstructed and reassembled. By turning these elements into dazzling performance objects, sculptures, and outfits,

Villalobos creates space for new queer expressions using materials that traditionally symbolize machismo. For Villalobos, it’s imperative to address the highly specific experience of Latinx border life as one so intimately tied to the culture of northern Mexico— an experience that is distinct from other Latinx communities of the West. “People don’t understand that the border dynamic is its own thing,” says Villalobos, noting El Paso’s unique, insular character.

Villalobos observes that El Paso can be conservative—it is home to generations of families who settled in the United States but remain close to Mexico and its Catholic or evangelical values. “It’s very old-school. Growing up, I had to silence my voice to feel safe,” he recalls, while also noting the “dangers of silence,” mainly to his emotional health. However, Villalobos is also committed to reclaiming some of the most characteristic aspects of El PasoJuarez culture through his performances and installations, immersing himself in its materials and sensibilities that are closely tied to the land. While his art is emotional and visceral for any audience, it is also saturated with coded meanings that resist translation. He relishes and digs deeper into regional specificity.

For example, Villalobos ties a blade to the back of his foot as one would tie it to a rooster before a cockfight, both acknowledging

Elle Pérez; Vincent, 2020-2021. Courtesry of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles.

the violence resulting from this as well as the tenderness in the deeply contradictory relationship between an animal and its owner. While it can be difficult for most audiences to understand, Villalobos’s image holds an entire set of emotions and associations for people raised within the culture. As with many of his Latinx contemporaries, Villalobos is unbothered by the perceived inaccessibility of his work. It is a privilege earned by the labor of previous generations of Latinx artists. He chooses to do as Aguilar did decades ago and immerse the self in the homeland and its environs.

Instead of addressing monolithic identity issues, these artists delve into personal histories of their inherited and chosen communities.

Giving life to new visual landscapes, the most recent work of the photographer and Bronx native Elle Perez offers a fresh perspective on the ways in which the queer body inhabits and belongs to a place. Unlike in their earliest images, Perez foregrounds natural environments—bodies of water, foliage, rocks—often minimizing the human form to the point of seeming absence. However, the perspective from which the world is viewed and shaped is intimately queer, Latinx, and very embodied. “Things become possible when shaping images with light, when a figure is in conversation with light. Plants are modified, the relationship to the body shifts, especially around queerness,” says Perez. Using a large-format camera, Perez focuses their attention on palm and cypress trees, for instance, as an approach to “talking about the experience of the body—but not necessarily from looking at a body.”

Even from the days in the early 2000s as a young photographer visiting punk scenes and underground wrestling matches in the Bronx, Perez gave intimate views into unseen worlds inhabited and shaped by young and often queer people of color. In play, sex, or violence, Perez’s subjects tested their bodies and forged inventive ways of being in the world. Perez remembers that back then, when images of Latinx and queer people were rare, they felt a responsibility to make work that helped fill this void. “When I was much younger, I was thinking a lot about representation.

That was really important to me.” Since then, many other artists via the Internet have produced a burgeoning body of photography that has allowed queer and non-cis-male people to see themselves. Unburdened of the labor of representation that is currently shouldered, shared, and lightened by many other artists, Perez is free to think about their own art in a different context. “Now I can talk with a certain level of opacity. I can work with gender malleability explored formally,” they explain.

In Aguilar’s life and images, Perez is able to locate themself in a lineage of Latinx artists: “I can identify my specific ancestors, and I can also measure our progress.” Perez and other Latinx artists remember Aguilar as they recognize their own struggles and journeys. Like the water and the rocks, the sand and the willows, Aguilar’s legacy is carried on in the manifestations of Latinx artists who continue to shape the world today.

Carribean Fragoza is a writer based in Los Angeles and the founder of the South El Monte Art Posse, a multidisciplinary arts collective.