"However much attenuated from the mortal flesh of the original, a painted portrait should take on a corporeal life of its own."

To make something new you must thoroughly understand the past — that way, you can sense when you are pushing into virgin territory. Just 27 years old, Coady Brown has surveyed the landscape of painting and wandered into a disco the German expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner never visited, although the well-dressed swells in his early-twentieth-century street scenes of Berlin were surely heading that way. On their journey to the now, they might have passed Otto Dix’s 1926 portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden, in checkered dress with monocle, cocktail, and cigarette, or Max Beckman’s patterned bathers and geometric waves in 1924’s Lido.

Brown’s paintings from the last two years — she completed much of the work on view during a residency this past summer at Maine’s Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture — channel the compositional velocity and colorful fatalism of those visions from the anxious times surrounding World War I and the Weimar Republic. Her figures are palpably present but unsettled, as if freeze-framed in varying postures by multihued strobe lights.

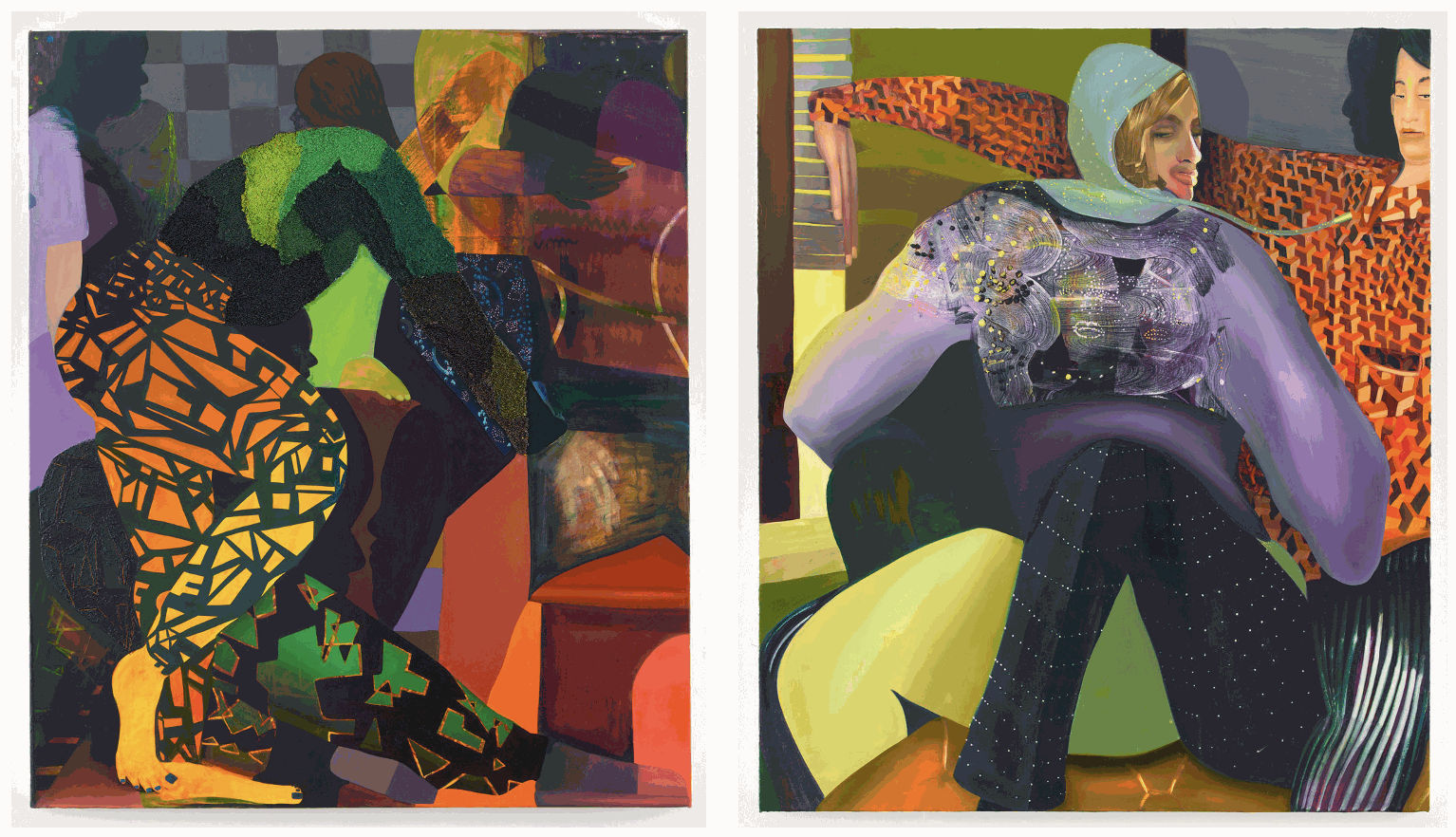

Coady Brown, Low Down, 2017 (Left) and Coady Brown, Fooled, 2017 (right). Courtesy of the artist and 1969 Gallery.

The swiveling heads, blurred limbs, and flaring cigarette of Brown’s Low Down may represent the collisions of desire on a dance floor; or perhaps the bent knee of the central figure signals the bravado of a reckless cyclist. Is it a simple graphic coincidence that the word IF emerges from the jagged pattern of a pant leg? Is there a more loaded word in the language? IF you do that, then this happens, IF you do this, then that happens — which choices lead to what consequences?

The paintings Creep and Fooled offer no clear answers, but, as with club denizens passing in the night, one senses emotions and attractions ranging from a come-hither smile to a nauseated grimace, from draped limbs to an over-the-shoulder dismissal. In Brown’s demimonde, a face might droop like a melting Dali clock even as fabric patterns take on the architectonic illusions of Bridget Riley’s 1960s op art.

In Cornered, heads overlap, reflect light upon one another, and mingle like projected slides. Brown’s colors are garish but exquisitely balanced with swathes of black and gray, by turns cool and warm. Space warps and folds like painted paper, with judiciously deployed highlights and subtly curved lines imparting bodily heft to these characters who might be both kissing and arguing. In Insomnia, beady eyes stare hopelessly at shards of shadows that hang overhead like broken dreams. The petal pattern on the pillow segues into rounded pills, though whether cause or cure is unclear.

Coady Brown, Insomnia, 2017 (left) and Coady Brown, Good Girl, 2016 (right). Courtesy of the artist and 1969 Gallery.

Brown’s lively tableaux might have a viewer flashing on, among others, Howard Hodgkin’s confectionary textures, Bob Thompson’s garish bacchanals, Marsden Hartley’s anthropomorphic emblems — yet she has found a quicksilver solidity that is uniquely her own. In the gorgeously complex Double Lover, we see a painting with roots in the old modernity of abstracted figures that is also aware of recent technology — the sense of a transparent Photoshop layer here, a polygon filter there. Ultimately, though, these faces are all about the timeless enigma of portraiture — think of Rembrandt intently studying his image in a mirror in order to paint himself staring back at us, or Francis Bacon appropriating Velazquez’s portrait of Innocent X for his screaming pope canvases.

However much attenuated from the mortal flesh of the original, a painted portrait should take on a corporeal life of its own, and Brown has rather amazingly pulled off the trick of entwining her interracial couple with, of all things, a rainbow. This blurred spectrum also adds convincing movement to her lovers, as if they were at first meeting our gaze, but then the very act of dragging the brush across the canvas abruptly turned their heads. The rainbow falls into shadow as it passes through the woman’s hair, and we may wonder what disturbance is registering on her ghostly, turpentine-scrubbed face. There is an engaging intimacy here — she leans back into the crook of her lover’s legs — of a piece with Brown’s other visions of interlaced torsos and arms and legs. Like her antecedents, Brown is an emphatic painter who is attempting to capture the zeitgeist in a bottle — these youthful bodies feel very much at home in a Lower East Side gallery — and it will be fascinating to see how this work ages. As with the Weimar painters, there is a fin de siècle quality. What could be more appropriate for our increasingly agitated moment?